The natural solution

Yasushi Ogawa, Japan’s only physician of Tibetan medicine, offers an alternative path to the Sustainable Development Goal of good health and wellbeing. Io Kawauchi meets him

Mori no Kusurijuku (“The Medicine School in the Forest”) stands in the foothills of the Nagano Prefecture city of Ueda, next to the historic Shioda Minakami Shrine. This extraordinary pharmacy was established in 2016 by Yasushi Ogawa, Japan’s only Amchi, a doctor specializing in Tibetan medicine.

Tibetan medicine is known as one of the four major branches of Eastern medicine along with Chinese, Indian, and Islamic traditional remedies, and medicinal herbs are at the core of its therapeutic methods. Amchi doctors themselves climb the steep mountains of the Himalayas, harvesting medicinal herbs. They then examine patients by evaluating their pulse and urine, and prescribe medicines from a selection of up to 200 kinds of pills made from herbs.

A graduate of Tohoku University’s Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences and a licensed pharmacist, Dr. Ogawa’s first encounter with Tibetan medicine came when he randomly picked up a book on the subject at a store. In 1999, his growing interest in the practice led him to Dharamsala, India, where the Tibetan government-in-exile is based. Two years later, at the age of 31, he became the first non-Tibetan to be admitted to the Men-Tsee-Khang, the Tibetan Medical and Astronomical Institute, where he studied for six years and qualified as an amchi.

At the age of 31, Dr. Ogawa became the first non-Tibetan to be admitted to the Men-Tsee-Khang, the Tibetan Medical and Astronomical Institute

Yasushi Ogawa was the first non-Tibetan to be admitted to the Tibetan Medical and Astronomical Institute | Keisuke Tanigawa

Yasushi Ogawa was the first non-Tibetan to be admitted to the Tibetan Medical and Astronomical Institute | Keisuke Tanigawa

A culture of compassion

A licensed pharmacist who is also well versed in herbal medicines, Ogawa’s pharmacy draws a wide variety of customers. No matter who he’s serving, Ogawa emphasizes an ethos of “caring and sharing”—paying attention to others’ needs while sharing knowledge, experiences, and feelings.

“People who receive treatment of any kind feel relieved. That’s a feature of medicine in Japan that hasn’t changed”

“In Japan, people used to wrap mugwort around burns,” Ogawa says. “Whether that really helps or not, I think it’s based on the desire to care and share when someone isn’t feeling well. People who receive treatment of any kind feel relieved. That’s a feature of medicine in Japan that hasn’t changed with the times.”

This spirit of mutual aid is not limited to Japan. “The Tibetan society I was part of had a very strong sense of caring and sharing,” says Ogawa. “Tibetans are an ethnic minority, so by necessity they help each other to survive.”

Ogawa experienced this first hand during his student days at the Men-Tsee-Khang. When a fellow student was struggling during a test, those around him would secretly help him. On one occasion, a teacher saw Ogawa writing down the wrong answer on an exam and told him, “Hey, you’re wrong here.”

The Mori no Kusurijuku is visited by people from all over the country | Keisuke Tanigawa

The Mori no Kusurijuku is visited by people from all over the country | Keisuke Tanigawa

Cheating, or an admirable attitude of not abandoning those in need? There’s an important social context to consider—Tibetans in Dharamsala, where the Men-Tsee-Khang is located, are refugees. And nowadays, many cancer patients visit Tibetan doctors in search of this culture of compassion.

“There’s no hard evidence that Tibetan medicine works against cancer,” says Ogawa. “But the local amchi accept patients and do the best they can. They don’t hesitate to reach out to those who need help. I believe that these patients are there precisely to receive care-and-share treatment, which is different from modern medicine.”

There exists a similar culture of caring and sharing in rural Japan. When Ogawa goes to give lectures in such areas, he often hears people say things like, “In the old days there were no medicines, so people would consume a brew of dried earthworms when they had a fever.” Surprisingly, antipyretic medicines made from earthworms (diryu) are still sold over the counter in Japan.

“Until 1961, when Japan’s universal health care system was established and the mass production of medicines allowed for stable supply, medicines were scarce”

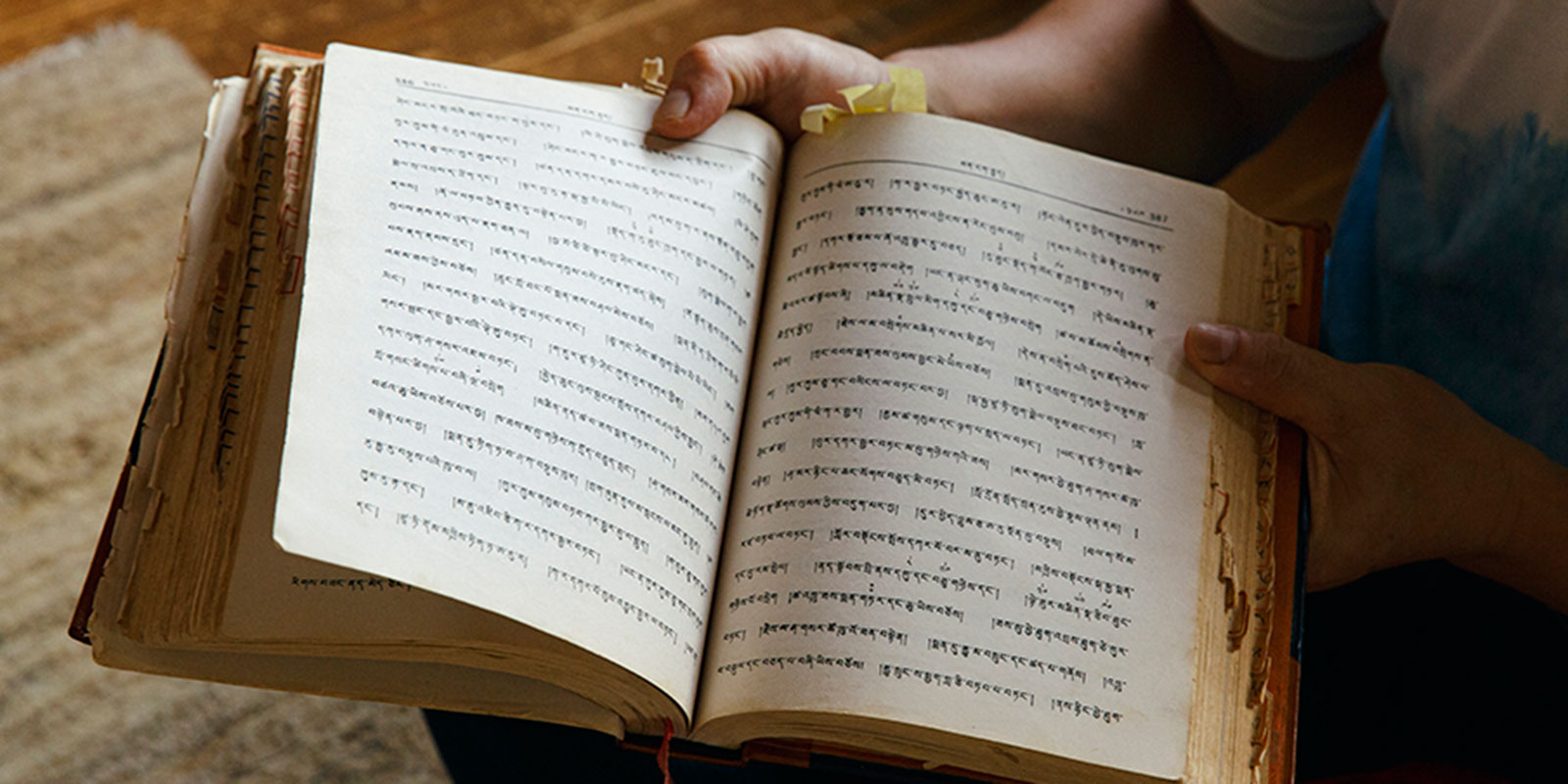

One of Yasushi Ogawa’s Tibetan medical textbooks | Keisuke Tanigawa

One of Yasushi Ogawa’s Tibetan medical textbooks | Keisuke Tanigawa

“Until 1961, when Japan’s universal health care system was established and the mass production of medicines allowed for stable supply, medicines were a scarce commodity,” says Ogawa. “So people had to depend on things like worms. I take over-the-counter medicines [made from worms] myself, and they work very well.”

This ancient culture of caring and sharing, which has since evolved in order to maintain social relationships amid economic development, may help explain Japan’s high life expectancy. Ogawa notes how social epidemiologist Ichiro Kawachi, currently a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, argues in his writings that the traditional lifestyle and local community ties in “a close-knit society with little inequality” is the reason for Japanese longevity.

The long game

Although everyone in Japan has access to the benefits of modern health care, more and more medical professionals and people concerned about their health are visiting Ogawa for advice. Perhaps they are drawn to the kind of traditional characteristics of Japanese society praised by Kawachi, which appear to be under threat as rural areas suffer from the declining birthrate and the aging population.

Yasushi Ogawa | Keisuke Tanigawa

Yasushi Ogawa | Keisuke Tanigawa

“People come here for frank opinions. I hope to continue to be a place of refuge, independent of authority and power”

The day before our interview, a person living with diabetes came to the Nagano pharmacy and left two hours later with a smile on his face. Although medicines containing herbs selected by Ogawa are sold at the pharmacy, all Ogawa did on this occasion was simply to listen carefully to the patient’s concerns and share his observations. “I don’t belong to any institution,” Ogawa says. “I think that’s why people come here for frank opinions. I hope to continue to be a place of refuge, independent of authority and power.”

“People come here for frank opinions. I hope to continue to be a place of refuge, independent of authority and power”

With the average lifespan in Japan expected to keep increasing, discussions are turning toward “health expectancy”—not merely longevity, but the ability to live a full and healthy life for as long as possible. When considering the future of health expectancy, there may be some clues to be found in the efforts of Japan’s lone amchi.