Smarter transport for more-livable metropolises in Southeast Asia

A pilot project in Bangkok epitomizes Japan’s contributions to sound development in the region

Thais are working under the banner Thailand 4.0 to transform their land into a high-income nation by 2030. Severe traffic congestion in Bangkok epitomizes the development bottlenecks that beset the nation, and optimizing transport there and in other Thai cities is a central plank in Thailand 4.0 planning. Japan is taking part in fulfilling the aims of that endeavor.

The biggest transport challenge for urban planners in Bangkok is the gulf between the city’s mass transit systems and the webs of soi side streets along which most of the population resides. Researchers from 11 Japanese and Thai universities and research organizations have demonstrated exciting potential for bridging that gulf. Their solution includes connecting the side streets seamlessly to rail and bus corridors through vehicle sharing with small electric vehicles.

Supported by Japanese and Thai governmental agencies, the researchers conducted a five-year pilot project in Bangkok from 2018 to 2023 and have since built on the project findings in follow-up proposals. Their work has yielded valuable findings that will be applicable throughout Southeast Asia.

A research model named for

an urban thoroughfare

Thailand 4.0 centers on digitization and innovation, and the participants in the research project introduced here named it Smart Transport Strategy for Thailand 4.0. The stretch of the central Bangkok thoroughfare, Sukhumvit Road, that served as the venue for the project lent its name, meanwhile, to their research model. That model shifts the focus of transport policy from building roads and railways to addressing residents’ diverse needs. Its practitioners use AI to steer people to optimal modes of transport, such as walking, personal mobility, and mass transit, across ever-changing combinations of time frames and destinations.

With the Sukhumvit Model, the researchers moved beyond theory and proved in a real-world setting that data-driven transport reduces carbon emissions and congestion. Validating the model in a high-traffic district provided the government with a scalable roadmap to replicate its success across other Thai cities. The results have lent important momentum to fulfilling Thailand 4.0.

Engendering positive expectations of the project were examples of substantive improvements in mobility in Bangkok in recent years. Most notably, a rail transit system has lured commuters away from automotive transport, and an expressway has lightened the burden on local streets. Bangkok’s urban rail network carried some 1.2 million passenger trips per day in 2024, according to Krungsri Research, and the expressway network carried more than 1.1 million vehicle trips per day, according to Bangkok Expressway and Metro.

Quality of life and

mobility as a service

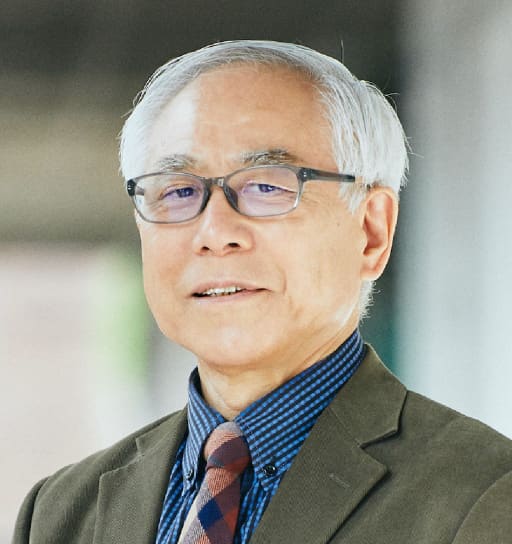

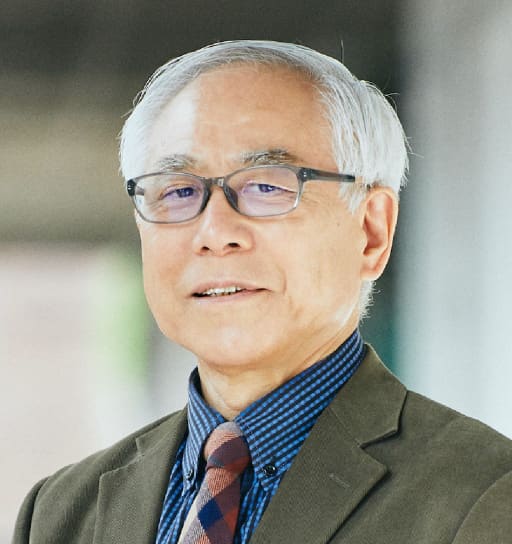

Dr. Hayashi Yoshitsugu,

now at Tokai Gakuen University

Serving as the Japan-side leader of the research project was Dr. Hayashi Yoshitsugu, then a professor at Chubu University’s Center for Sustainable Development and Global Smart City, in Aichi Prefecture. Hayashi characterizes the Sukhumvit Model as “an integrated tool for structuring hierarchically the transport infrastructure that links the Sukhumvit District and the rest of Bangkok.”

“The Sukhumvit Model,” explains Hayashi, “advances the principles of quality of life and mobility as a service and transforms residents’ travel options in ways that let them choose the best time sequence for travel, work, and other activities. Along with enhancing quality of life, it reduces traffic congestion, carbon dioxide emissions, and air pollution.”

Dr. Thanaruk Theeramunkong

Serving as the Thailand-side leader of the research project was Dr. Thanaruk Theeramunkong, a professor at Thammasat University’s Sirindhorn International Institute of Technology (SIIT). “We cannot realize a high-value economy,” emphasizes Thanaruk, “if our logistics costs are high or if our workforce loses hours in traffic. Therefore, the government views smart mobility not as a luxury but as a critical infrastructure requirement for national competitiveness.”

The emphases described by Hayashi and Thanaruk are pertinent to settings beyond Bangkok. Their project colleague Dr. Pawinee Lamtrakul, an associate professor and the director of the Center of Excellence in Urban Mobility Research and Innovation at Thammasat University, elaborates.

“We are offering a practical framework for pursuing economic growth while strengthening social equity, climate resilience, and long-term urban livability across Southeast Asian cities. I expect the Sukhumvit Model to support policies that promote compact and green urban development, inclusive street design, and flexible work–travel patterns through tools that integrate quality of life and mobility as a service.”

Operational, social, environmental,

and user-acceptance considerations

Developing Smart Transport Strategy for Thailand 4.0 included investigating the viability of a community-based ride-sharing service to substitute for private cars. Three small electric vehicles deployed by the researchers supplemented first- and last-mile mobility at three condominium buildings that house about 250 residents.

Among the researchers was Dr. Chou Chun-Chen, now an assistant professor in the Division of Sustainable Energy and Environmental Engineering at the University of Osaka. Chou relates how she and her colleagues managed the experiment and how they interpreted the results.

“Underlying our interest in substituting for private cars were the mobility challenges posed by Thailand’s soi—narrow residential streets prone to chronic congestion, increasing air pollution, limited modal choices, and weak connectivity to public transport. Our team integrated operational design, social and environmental impact evaluation, and user-acceptance analysis to ensure that the proposed solution would be both technically feasible and socially meaningful.”

Beyond traditional

cost-benefit analysis

Hayashi underlines another crucial aspect of the human dimension in optimizing mobility: demographics. “Population decline,” he stresses, is an inevitable constraint on all aspects of public policy in Thailand, just as it is in Japan. We need to shift from a focus on people as tools for economic growth to a focus on economic vitality as a means of enriching life.”

“Conventional transport models,” adds Thanaruk, “are primarily engineering centric. They attempt to optimize traffic flow and road capacity. In contrast, models that incorporate quality of life by applying the Quality-of-Life Accessibility Model developed by Professor Hayashi are human centric. Instead of focusing solely on the vehicle, they position the urban user’s time and quality of life as the central focus.”

Dr. Pawinee Lamtrakul

Pawinee helped develop a people-centered performance indicator that transcends conventional metrics, such as travel time and traffic volume. “I worked on linking spatial design, transport infrastructure, and travel behavior,” she explains, “with the subjective perceptions of commuters in Bangkok. That included defining such quality-of-life domains as health, neighborhood environment, leisure life, housing conditions, and work-life balance and translating these into measurable indicators.”

Proactive coordination and

mutual respect

Thanaruk speaks eloquently on how the project participants managed the bilateral cooperation productively. “The Japanese research culture is architectural,” he muses, “focusing on meticulous planning and rigorous standards. The Thai approach is highly agile. We specialize in navigating the rapid, complex reality of Bangkok’s streets. The challenge was bridging the gap between our Japanese colleagues’ structured planning and the dynamic local environment. We overcame that challenge by establishing a hybrid workflow where we played to our respective strengths.”

“I worked with Thai and Japanese researchers in the pilot project,” recalls Chou. “We needed to harmonize theoretical ideas with practical solutions that were workable in a Thai context. The various inputs were complementary and fortified the research.” “Mutual respect, open communication, and a shared commitment to societal impact were essential,” adds Pawinee, “in aligning our approaches and producing outcomes that are both scientifically robust and socially meaningful.”

Dr. Chou Chun-Chen

“Cross-border cooperation in smart transport,” concludes Thanaruk, “goes beyond just connecting roads or railways. It is about connecting intelligence and opportunities. We have been successful in cross-discipline fusion cooperation between quality-of-life policy researchers in Japan and AI application researchers in Thailand. Ultimately, we are not just connecting roads. We are building infrastructure for shared prosperity.”

The stance and vision expressed by Thanaruk characterize Japan’s approach to contributing to sound development in regions around the world. That approach has supported advances in such domains as education, medical care, industry, civil administration, infrastructure, and—as in the example introduced here—transport.